Public Matchmaking in a Competitive Esport

Skill-based matchmaking (SBMM) is the devil. At least if you are an above-average player trying to pubstomp in a match of a recent Call of Duty game. The most popular title of the series, Call of Duty: Warzone, is especially haunted by fierce discussions regarding the extent to which matchmaking is based on player skill. And if you see SBMM as the devil of your gaming experience, engagement optimized matchmaking (EOMM) is an attempt to maximize your time in hell by granting you the occasional bot lobby.

[Click here for the Reddit link of this post (455 upvotes, 128 comments)]

While the quick rise of sites like sbmmwarzone.com shows players’ interest in these concepts, empirical analyses of SBMM in Warzone are very sparse (see Xclusive Ace’s video for the best analysis to date) and, to my knowledge, non-existent when it comes to EOMM. Moreover, Warzone tournaments with huge prize pools have become a weekly regularity despite players essentially being at the mercy of a matchmaking black box that determines the difficulty of the competition.

I want to do my part in filling this gap by employing the newly available data on Warzone lobby strength. Using players’ past Warzone matches and stats obtained from cod.tracker.gg (battle royale only) and looking up the respective lobby strength (median team KD) with sbmmwarzone’s match search feature, I employ regression analyses and other statistical tools to test SBMM and EOMM in Warzone. Here are the results:

SBMM

For this section, I use the past 220 Warzone matches of 10 players (1,929 matches in total after excluding non-BR modes) with each player representing a tenth of the overall KD distribution, i.e. one player from the top 10%, one from the next best 10% etc. All players have already accumulated substantial playing time ranging from 5.4 days to 41.4 days which ensures that we don’t have any “beginner lobbies” in our sample.

Looking at the relationship between player KD and corresponding lobby strength, there can be no doubt about the existence of SBMM in Warzone. Restricting the analysis to the players’ solo games (154 games in total), the correlation between a player’s KD and average median lobby KD is 0.9174 and the p-value of the coefficient estimate when regressing median lobby KD on player KD is 0.000000007%.

This minuscule probability corresponds to the likelihood of getting the results at hand if player KD would have no systematic effect on lobby strength. In other words, SBMM not being in the game is roughly as likely as Activision finally fixing all Hk:s and DEV errors.

Key Takeaway Nr. 1:

Player KD has a positive and highly statistically significant impact on lobby strength.

Unfortunately, it is not possible to identify which player stat has the strongest impact on skill-based matchmaking since the “skill stats” of a player are highly correlated with each other (KD and score per minute (SPM), for example, have a correlation of 0.9128 in this sample). This means that players with a higher KD will most likely also have a higher SPM. Therefore, if these players get harder lobbies, we won’t know if it’s because of the higher KD or the higher SPM since both is always the case simultaneously.

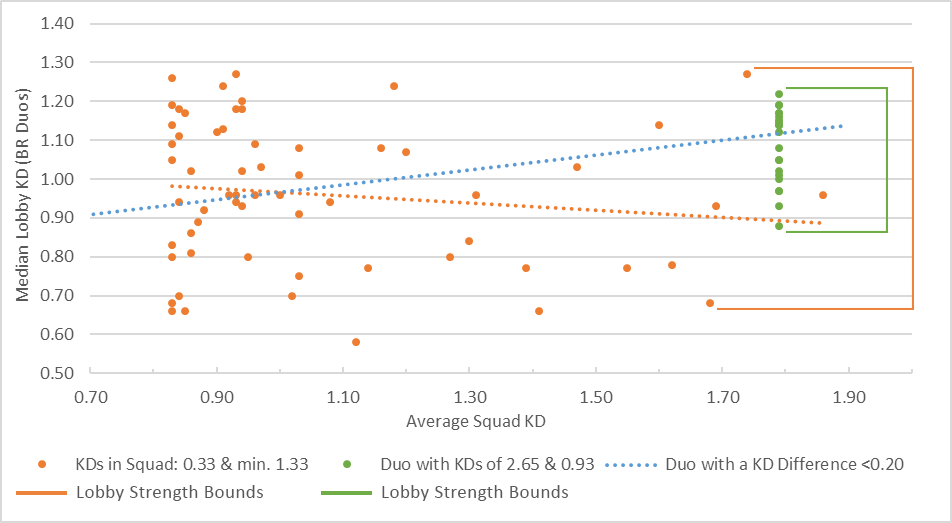

What we can examine, though, is the interplay between individual player KD and the average KD of their own squad. If we pair a 0.3 KD player with a 1.7 KD player (average squad KD of 1.0), will their lobby strength correspond to the skill bracket of players with a KD of 0.3, 1.7 or 1.0? The answer is yes. To see that, I first transform the trendline of Figure 1.1 to its BR Duos equivalent by using the median lobby KDs of duos containing two roughly equally skilled players (absolute KD difference lower than 0.20). We again see a positive and statistically significant impact of their squad KD on lobby strength.

In addition, I include the observations of the player with the lowest KD in my sample (KD of 0.33) when they are paired with a player that has a minimum KD of 1.33. The result is that their average squad KD has no statistically significant influence on the strength of the lobbies they get (the slope of the trendline is even negative in this case but, as I said, not statistically significant).

The fact that there are so many different average squad KDs for that player suggests that they mostly play BR Duos with a random partner, eliminating the discussion about the influence of who is the host of the lobby search.

Key Takeaway Nr. 2:

When players with different skill levels team up, their average squad KD has no direct influence on lobby strength.

So what is then the effect of teaming up with a relatively lower skilled player? Another example from my data helps to shed more light on this question. In this final extension of Figure 1.1, I add the lobby strength observations of a duo with KDs of 2.65 and 0.93 whose average KD of 1.79 falls close to the observations seen for our previous player.

It seems that the SBMM system creates bounds of potential lobby strength that are based on the individual “skill brackets” of the players inside a squad (see how the lowest/highest median lobby KD for our 1.79 KD duo is markedly higher/lower than that of the duos with similar average KDs that contain the 0.33 KD player and a 3.0+ KD player).

In essence, this means that two players with a KD of 1.70 will, on average, play in harder lobbies than a squad containing a 0.30 and 3.10 KD player, despite both teams having an average squad KD of 1.70. For squads of more than two players, the influence of an individual player’s skill on these lobby strength bounds is probably diluted since more players are being considered during the matchmaking process.

Key Takeaway Nr. 3:

The individual skill levels of the players inside a squad determine the bounds of lobby strength in which most matches will occur.

After finding convincing evidence for the existence of SBMM, the next part will deal with the issue of EOMM in Warzone.

EOMM

In order to test EOMM, we need a context that is described by a constant level of skill-based matchmaking. In such an environment, any systematic variability in lobby strength cannot be explained by differences in SBMM which, in turn, opens the door for alternative explanations. Otherwise, we won’t know whether bad match performances lead to player disengagement which grants easier lobbies based on EOMM or if bad performances simply occur more frequently for lower skilled players that get easier lobbies due to SBMM.

We achieve this context of constant SBMM by looking at matches of the top 0.1% of players. Players with a KD of 5.0 cannot get much stronger lobbies than 4.0 KD players since there are simply not enough players good enough that could be used as differentiating factors in their respective matchmaking processes.

Indeed, player KD is not statistically significant anymore when analyzing its influence on solo lobby strength of top level players. The matches used for this test and for the remainder of this section come from the past 500 matches of 10 highly skilled players (4,743 matches in total after excluding non-BR game modes) with KDs ranging from 4.16 to 5.70. These players include 4 popular streamers from the US (Huskerrs, Nickmercs, Tommey, Swagg), 4 popular EU streamers (Jukeyz, Vapulear, Falaxii, Shukz) and 2 random players from the top of the codtracker leaderboards (Dakeeve and Beastlyy) in order to also include lesser-known elite players in the sample.

Providing some first anecdotal evidence for EOMM, my friends and I noticed that our last game of the day tends to be easier than all of our previous matches. Is this Activision predicting when we will end our session and trying to entice us to play on by baiting us with easier lobbies? We usually end our sessions at around 3-4am (don’t judge our sleep schedules), so maybe this is simply a side effect of this specific playing time?

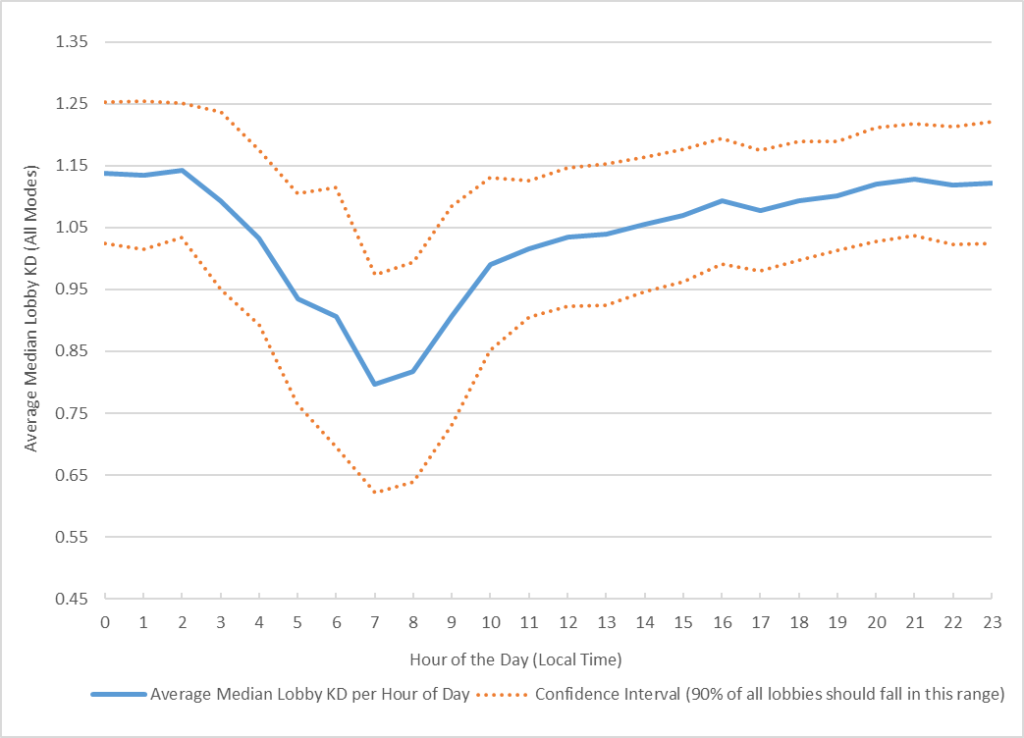

To analyze this phenomenon in more detail, I use the aforementioned matches of the 10 elite players (restricted to matches where the average KD of their squad is at least 3.50 to avoid most “Random Duos/Trios/Quads” matches) and calculate the average median KD of their lobbies for each hour of the day (in local time). Even if they don’t host each of their lobby searches, they will probably play most games with teammates living in rough geographic proximity to them. This means that their local time should be a good approximation for the local time of the hosting player.

The results of this test are astounding and have huge implications for organizers of future Warzone tournaments. The average lobby strength stays at similarly elevated levels from 8pm to 2am (the diamond lobbies you would expect from a squad filled with elite players). From 3am to 7am, however, there is a steady decline in lobby strength that reverses again from 8am onwards. The same pattern can also be seen in my first sample of matches from players of all parts of the KD distribution. What the hell is going on here?

Any SBMM system probably tries to optimize three things: player ping, matchmaking time and player skill levels. My guess is that the huge reduction in player base from 2am to 7am strongly impedes the first two aspects (it takes longer to find enough players near you to create a match) which then gets compensated by a reduced effort to find players with matching skill levels.

While this is logical, it seems exceptionally unfair to organize Warzone tournaments across majorly different time zones in which each squad is searching their own lobbies (e.g. 3vs3 or 4vs4 kill races). It seems hugely irresponsible to let people compete against each other for large prize pools with one half sweating in lobbies that have an average median KD of 1.14 while the other half is breezing through median lobby KDs of 0.79. Watching such tournaments in the future will definitely leave a bad taste in my mouth.

Key Takeaway Nr. 4:

Skill-based matchmaking is at its strictest from 8pm to 2am and gets toned down massively from 3am to 7am (all local time).

Nevertheless, identifying this SBMM prime time provides a fitting context to further test our EOMM hypotheses. If we find systematic occurrences of bronze lobbies during the times where SBMM should be at its strictest, it will be hard to argue against the existence of another type of matchmaking system besides SBMM.

Unfortunately for all EOMM enthusiasts, there are only 10 bronze matches during this time vs. 55 outside of the SBMM prime time. I can identify 7 of them as being played in a squad with players from both the US and Europe, mostly wagers of Tommey against CPentagon, Fuzzn, Vapulear and Lenun. While his local time was inside the SBMM prime time, the Europeans were already inside the weaker time periods of SBMM which, if they hosted the respective matches, provides a consistent explanation for the reduced lobby strength. The other 3 bronze lobbies don’t provide a large enough sample size to perform any sensible tests on and are probably just outliers in the usual distribution of lobby strength based on SBMM.

Even though we cannot find large systematic deviations in median lobby KD during the SBMM prime time, EOMM could be more subtle and only grant slight but predictable reductions in lobby strength based on player disengagement. This will be tested in the following part:

Using the elite players’ matches (examining all BR modes as well as only BR Solos) during the SBMM prime time (8pm to 2am), I test whether lobby strength is affected by player engagement as proxied by…

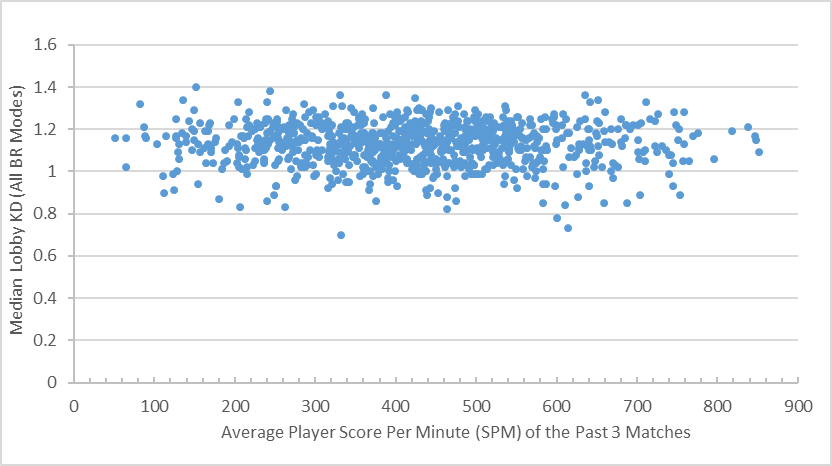

…a player’s recent performance:

No, I cannot find evidence that recent player performance has a significant effect on lobby strength when computing performance based on average kills/deaths/KD/damage/damage per minute/score/score per minute/life time/placement using each player’s past 3 matches. Extending the computation window to the past 5 matches shows the same results.

Being on a losing streak also has no significant impact on lobby strength. Matches following a win are also not significantly different to other matches in terms of difficulty.

Some exemplary figures:

This does not mean that playing poorly for a long period of time to the point of actually tanking your lifetime KD, SPM etc. won’t have an impact on your lobby strength. It just means that organic short-term performance deviations, that should correlate with player engagement, don’t yield the significant results needed for an EOMM-based interpretation.

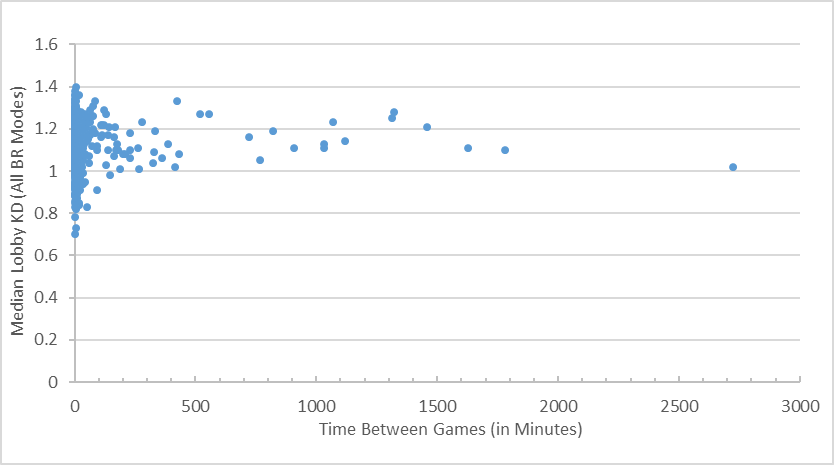

…the elapsed time between matches (suggested as a disengagement proxy in the paper on EOMM by Chen et al. (2017)[1]):

No, there is no evidence that longer times between matches lead to easier lobbies. Maybe the disengagement factor needs a long one-time break to kick in? Still, the five games after a three day break (occurred for 3 players in the sample) are not significantly different to the other games played by the respective player.

…a player’s playing duration:

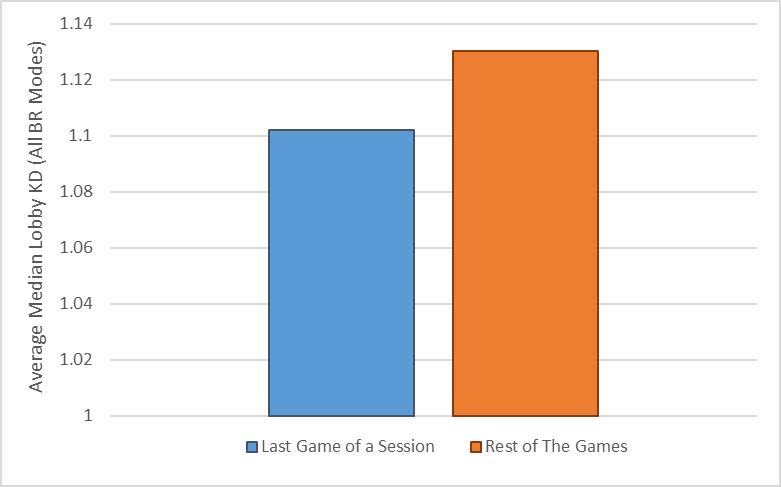

When I test the beforementioned anecdotal observation that my last game of a given session tends to be easier than the rest, I find some intriguing results. The last game of a player’s Warzone session (with a session being defined as a minimum break of 6 hours between games) is easier than the rest with a slight statistical significance (significant at the 10% level, if you are interested).

Practically speaking though, the median lobby KD of these last matches is, on average, only 0.03 KD points lower than the rest (i.e. a player with an average median lobby KD of 1.13 gets a 1.10 median KD lobby to end their session).

It might be tempting to be outraged by the manipulative character of a matchmaking system that predicts when you end your session and then tries to lure you into playing more by rewarding you with easier lobbies. However, this finding could also simply be the result of some players wanting to end their session with a good game combined with the fact that good games occur more frequently in relatively easier lobbies.

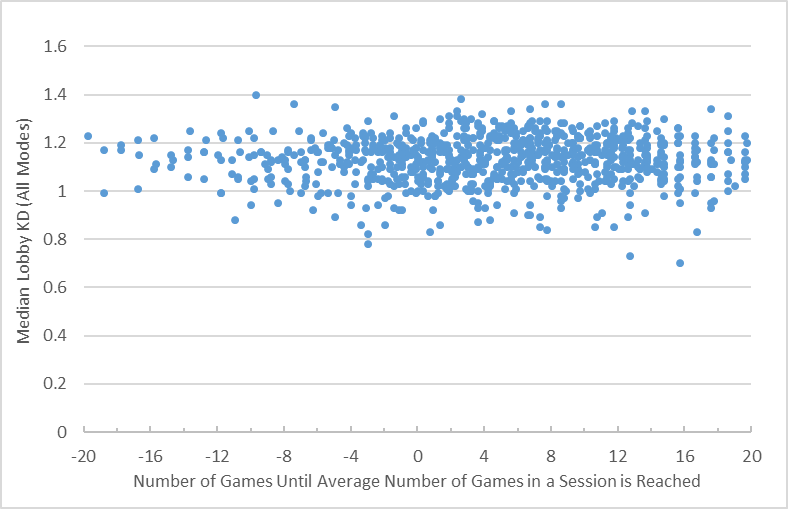

Using other variables of estimated playing duration for each player (average duration of a playing session, average number of games during a session) also yields no supportive evidence of an EOMM system that dynamically changes lobby strength based on a player getting closer to their usual playing end time.

Key Takeaway Nr. 5:

Using different proxies for a player’s engagement with the game, there is little supportive evidence for EOMM.

Conclusion

The matchmaking of Warzone is heavily influenced by player stats related to skill. While I cannot find conclusive evidence for the assumed characteristics of an EOMM system, we have to keep in mind: absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. It could be the case that the matchmaking system recognizes that these players tend to stay engaged with the game no matter the lobbies they get and so it sees no need to dynamically adjust lobby strength (but how do you identify and search for “easily disengaged” players to test whether their matches show evidence for EOMM?).

Moreover, EOMM could be solving such a complex optimization problem with respect to the engagement of all 150 players in the lobby that it becomes impossible to find systematic patterns of EOMM by looking at individual player data.

Still, I think there is definitely some use in these results. They provide a statistical reference that you can point to when your friends or your favorite content creators say things like “we got shit on in the last 5 games, EOMM will give us our bronze lobbies now”. Even more importantly, they show that before accusing content creators of being favored by SBMM, one has to first look at their playing schedules. It may well be that they simply play during times of low SBMM, something everybody could, for good or for worse, exploit.

TOP !!!

Great work